The Colorful World of Animation

A Short Story about DEFA Animation

Animation Studio

Exterior view of the former dance and dining restaurant Zum Reichsschmied in Dresden-Gorbitz; Photography: © DEFA-Stiftung

A greedy little devil who steals donuts and upsets an entire Punch and Judy show; a chubby Mr. Winter, who flees to the Arctic before the first rays of the sun; a pear girl who outwits a king; an old tortoise who travels to Paris to dance the can-can; and the mysterious, colorfully shimmering bird Turlipan—these are just five of thousands of characters that were created in the DEFA Studio for Animation Films. These characters attest to the skills of Dresden's animation film artists, their joy of discovery, their imagination and their love of storytelling. For three and a half decades they worked at the studio on the Gorbitzer Höhen and shot about 950 cinema animation films. The films used various techniques—silhouette films, cartoons, cut-out and puppet films, clay or sand animations—and were made with careful, often experimental manual work. Just as computer technology found its way into animation film production, the studio was closed.

How it all began...

On April 1, 1955, a decision by the Council of Ministers of the GDR came into effect, creating a legally and economically independent DEFA Studio for Animation Films in Dresden. The former dance hall and restaurant Zum Reichsschmied was selected as the location, as it had been converted into a studio and expanded in 1939/40 by the company Boehner - Reklame und Film. After 1945, Soviet occupation authorities handed the site over to DEFA, which had set up a branch of their Berlin headquarters there and, until 1954, mainly produced documentary and popular science films as well as work for the newsreel series THE EYEWITNESS REPORT.

DEFA were not in uncharted waters when they founded their own animation studio. Gerhard Fieber, who came from Deutsche Animation GmbH, had made four short DEFA animation films as early as 1946, including AN UNDERGROUND SCARE (U-BAHNSCHRECK), a satire of crowds and scramble in the Berlin underground, for the first issue of THE EYEWITNESS REPORT, and HANS KLEIN, a film commissioned by the SED party on the municipal elections. After a long break, several directors tried to revive the animation films within existing DEFA structures starting in 1952. For instance, Kurt Weiler, who had returned from exile in England, created the first puppet animation films alongside Johannes Hempel. Bruno J. Böttge continued the known German tradition of paper-cutting animation and silhouette film, particularly showing his admiration for Lotte Reiniger’s with the silhouette film THE WOLF AND THE SEVEN LITTLE KIDS (DER WOLF UND DIE SIEBEN GEISSLEIN, 1953). And Lothar Barke ventured into animation with CATERWAULING (KATZENMUSIK, 1954), a grotesque film about rock 'n' roll dancing youths. When these directors were asked to help setting up the new studio in Dresden in 1955, they agreed unreservedly, as did several graduates from the Burg Giebichenstein Academy of Applied Arts in Halle. The group included Otto Sacher, Helmut Barkowsky, Katja and Klaus Georgi as well as Christl and Hans-Ulrich Wiemer. The puppeteer Günter Rätz, who later became the father of the East German Sandman, Herbert K. Schulz, the inventor of the West German Sandman, and Gerhard Behrendt also came to Dresden. They all did pioneer work because animation technology was initially hardly available on the Gorbitzer Höhen. So they tinkered, planned and built until the first films made in Dresden were released in cinemas.

THE WOLF AND THE SEVEN LITTLE KIDS (DER WOLF UND DIE SIEBEN GEISSLEIN, Bruno J. Böttge, 1953) Photography: Bruno J. Böttge

CATERWAULING (KATZENMUSIK, Lothar Barke, 1954) Photography: Lothar Barke, Werner Baensch

According to a government order, 80 percent of the animation films produced in the studio had to be children’s films. Therefore, the possibility of adapting German sagas and fairy tales as well as new East German children's books was first on the agenda; in addition, there were self-developed, mostly didactic stories about everyday life of children and their parents. As everywhere else in the world, animal figures were used to demonstrate human characteristics and behavior, whereby Walt Disney's style was sometimes clearly recognizable: for example, in cartoons by Otto Sacher (A ROLLING STONE GATHERS NO MOSS (WER RASTET, DER ROSTET, 1956)) or Lothar Barke (THE BUNNY THAT DID NOT WANT TO LEARN (VOM HASEN, DER NICHT LERNEN WOLLTE, 1956)). Formal experiments were rare at the beginning of the studio’s work. Hardly any of the early animated films exposed themselves to the accusation of “formalism”—the overemphasis of form over content—as a counterpoint to “socialist realism.” And yet initial conflicts arose: for a while, Punchinello was dropped from the repertoire as a decadent figure. In addition, fairy tales by the Brothers Grimm were checked for socio-economic or class-struggle aspects, as in the case of a planned adaptation of "Hansel and Gretel" in which the dramaturgs insisted that the witch had to symbolize capitalism and Hansel and Gretel the militant proletariat at the end of the 1950s. In SLEEPING BEAUTY (DORNRÖSCHEN, Katja Georgi, 1967), the prince was not allowed to simply hug the princess after breaking through the thorn hedge but had to prove himself as a fighter against a dragon beforehand. Klaus Georgi's cartoon BLUE MICE DON’T EXIST (BLAUE MÄUSE GIBT ES NICHT, 1957/58), which playfully made fun of dogmatic views of the world and art, was temporarily threatened with a ban. The cut-out film IN MY VIEW (ICH SEHE DAS SO!, 1958) by Bruno J. Böttge, in which an abstract painter is denounced as a donkey, functioned as a political counter-project.

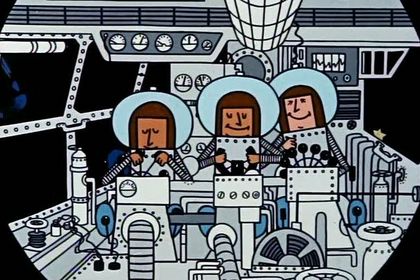

With some of the works declared as family films, DEFA also addressed contemporary social, political and technical developments. For example, Walter Später's hand puppet film TROUBLE AT THE STABLE (KRAWALL IM STALL, 1960) cheerfully pleaded for cooperatives in the countryside. Enthusiasm for space travel was also reflected in several productions: in the puppet animation film SHARP LEFT BEHIND THE MOON (GLEICH LINKS HINTERM MOND, Günter Rätz, 1959), Santa Claus is asked to find out what a Sputnik is; in OUTER SPACE ADVENTURES (ABENTEUER IM ALL, Hans-Ulrich Wiemer, 1959), doll children simulate a space flight with the help of a self-made rocket model; in the pointedly edited satirical cartoon THE SENSATION OF THE CENTURY (DIE SENSATION DES JAHRHUNDERTS, Otto Sacher, 1959/60), the U.S. efforts to beat the Soviet Union to the moon landing are taken for a ride. And in the puppet animation film PROXIMA CENTAURI ADVENTURES (UNTERNEHMEN PROXIMA CENTAURI, Jörg d'Bomba, 1962), four researchers fly to a neighboring solar system in a proton rocket to discover a plant-based growth hormone for terrestrial agriculture.

SHARP LEFT BEHIND THE MOON (GLEICH LINKS HINTERM MOND, Günter Rätz, 1959) Photography: Helmut May

THE SENSATION OF THE CENTURY (DIE SENSATION DES JAHRHUNDERTS, Otto Sacher, 1959-60) Photography: Walter Eckhold, Hans Schöne

In the early 1960s, the idea of building an elaborate new building for the Studio for Animation Films seemed almost utopian. The GDR government supported this project because some films made in Dresden had proven to be real hits as exports to western countries, but the existing premises hardly allowed for any expansion of production. A spacious studio with artists’ workshops, drawing rooms and editing rooms was planned: a kind of “factory for animation films" in which one could also produce film series and commissioned works paid in foreign currency. A landing for helicopters was even considered so that film material could be transported quickly to the only GDR duplication factory in East Berlin and back again. However, the plan failed due to the immense costs. So the animators had no choice but to optimize their existing manufactory-like work spaces.

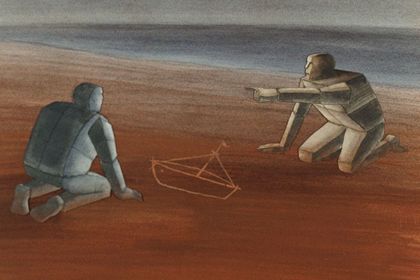

The creation of the first full-length animated puppet film proved that it was possible to achieve the extraordinary even under the conditions of a manufactory: in 1961, director Johannes Hempel produced THE STRANGE HISTORY OF THE PEOPLE OF SCHILTBURG (DIE SELTSAME HISTORIA VON DEN SCHILTBÜRGERN), an epic overall somewhat fussy adaptation of the classic chapbook, albeit with many quarrels and excessive costs. Only a short time later, the studio threw itself into its first extensive series production: after Günter Rätz had received awards at international festivals for his two films, THE RACE (DER WETTLAUF, 1962) and MEASURE FOR MEASURE (MASS FÜR MASS, 1963), French business partners tried to obtain a time-limited license for forty other films with the two pantomime wire characters Mr. Short and Mr. Long. The series received the international title FILOPAT & PATAFIL and soon took up the annual production capacity of the studio and the collaboration of several directors: Jörg Herrmann, Ina Rarisch, Hans-Ulrich Wiemer, Heinz Steinbach, Werner Krauße, Monika Anderson and others. In 1976/77, Günter Rätz worked together with Vivienne and Juan Forch, two Chilean exiles working temporarily at the Dresden Studio, on the last installment, a latecomer titled THE PROBLEM (DAS PROBLEM).

Filopat & Patafil: THE RACE (DER WETTLAUF, Günter Rätz, 1962) Photography: Helmut May

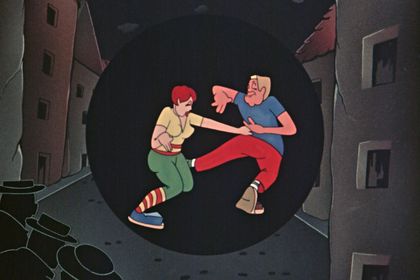

From the PUNCHINELLO series: PUNCHINELLO LEARNS TO PERFORM MAGIC (KASPER LERNT ZAUBERN, Hans-Ulrich Wiemer, 1974) Photography: Karl-Hermann Kootz

While FILOPAT & PATAFIL was designed for a more adult audience, many of the later series were created for young viewers, including the PUNCHINELLO series (KASPER, 1967-1979) by Hans-Ulrich Wiemer, Rudolf Schraps and Katja Georgi; the THE TEDDY WITH FURRY EARS series (TEDDY PLÜSCHOHR, 1971-1973) by Monika Krauße-Anderson, Werner Krauße and Barbara Thieme-Eckhold; the hippopotamus, dog and hedgehog stories (PUCK UND KATRIN, 1973-1979) by Ina Rarisch; the FROG series (FROSCH, 1979-1985) by Hans- Ulrich Wiemer or the HEDGEHOG series (IGELCHEN, 1984–1987) by Christl Wiemer. In the series EUREKA! (HEUREKA, 1973–1984), Helmut Barkowski, Lothar Barke and Rainer Hempel conveyed scientific principles through amusing stories. A series with two popular characters from the children's magazine Frösi had already been published beforehand: LITTLE CLEVER MAX PFIFFIG AND HIS FRIEND (MÄXCHEN PFIFFIG, Otto Sacher, Helmut Barkowsky, Hans-Ulrich and Christl Wiemer, Klaus Georgi, 1959-1970): two clever boys encountering a drunken sun, causing a mass crash in the Friedensfahrt (ride for peace), or struggling with a chaotic robot. One of the last series produced in the DEFA Studio for Animation Films followed the adventures of the cat Mausi and the dog Kilo. MAUSI AND KILO (MAUSI UND KILO, Hans-Ulrich Wiemer, Lutz Stützner, Christian Biermann, 1988/89) was created as a co-production with Czechoslovakia.

An exceptional director: Kurt Weiler

In the mid-1960s, Kurt Weiler, who had left the Dresden Studio in a dispute over aesthetic issues and had worked for DEWAG (German Advertising Agency) for a while, found his own refuge in the DEFA Studio for Short Films in Potsdam-Babelsberg. As a sort of “exotic” among the documentary filmmakers there, he repeatedly took risks in terms of both content and aesthetics. As early as 1954, he pledged in the magazine Deutsche Filmkunst for more courage in using imagery and alienation in animated films: "The facial expressions and movements of the puppet are stylized and concentrated. If you become naturalistic in the shape and direction of the puppet, then the justification of the puppet film ceases.”[1] He then tried to put this into practice. For his puppet animation films, some of which he also realized as a guest in Dresden, he secured well-known allies. They supported him in pursuing unconventional, non-naturalistic paths. For example, he brought in Achim Freyer, who trained at the Berliner Ensemble and was influenced by Bertolt Brecht, for scenographic work. In films like A FARMER AND THE GENERALS (EIN BAUER UND DIE GENERÄLE, 1960), FERDINAND (FERDINAND, 1964), THE BRAVE LITTLE TAILOR (DAS TAPFERE SCHNEIDERLEIN, 1964) or HEINRICH THE WANNABE KING (HEINRICH DER VERHINDERTE, 1965), Weiler and Freyer radicalized “the use of materials: iron filings, nails, lots of metal in general, that on the grainy, less sensitive ORWO color film looked startlingly exotic and strange."[2]

THE BRAVE LITTLE TAILOR (DAS TAPFERE SCHNEIDERLEIN, Kurt Weiler, 1964) Photography: Erich Günther

HEINRICH THE WANNABE KING (HEINRICH DER VERHINDERTE, Kurt Weiler, 1965) Photography: Erich Günther

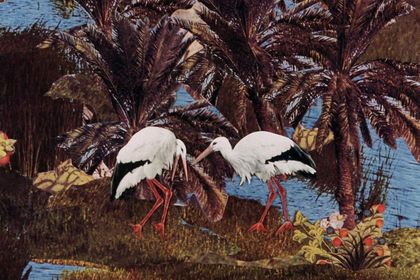

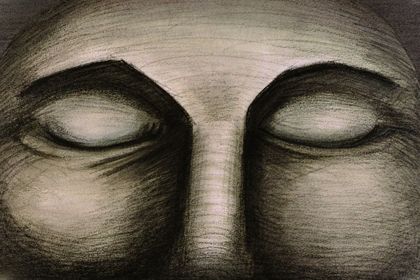

From then on, the director's artistic collaborators had included several East German avant-garde artists: Friedrich Goldmann created experimental music for A HEAD FILLED WITH IDEAS (FLOH IM OHR, 1970), an ironic commentary on the theory of convergence. The stage designer, theater director and poet Einar Schleef participated in the design of the puppets for THE PRESENT (DAS GESCHENK - EINE BEINLICHE GESCHICHTE, 1974), an excursion into the history of the Hohenzollern, with which Weiler polemicized against training young people for war. For this latter project, Schleef created heads that opened and could be cleared out. And for THE LION BALTHASAR (DER LÖWE BALTHASAR, 1970), an animal parable, Werner Frischmuth built a complete zoo out of empty boxes and packaging material. Like his great Czech role models Jiří Trnka and Jan Švankmajer, Weiler worked more for adults than for children and liked to explore philosophical terrain. In the puppet film NÖRGEL AND SONS (NÖRGEL & SÖHNE, 1967), he reflected on the origins and role of money; in THE APPLE (DER APFEL, 1969), he condensed the history of mankind from primitive society to the communist era into a compelling parable. In RECONSTRUCTION OF A FAMOUS MURDER CASE (REKONSTRUKTION EINES BERÜHMTEN MORDFALLS, 1975), the biblical story of Cain and Abel told as a flat-figure collage, Weiler collaborated with the stage designer Ezio Toffolutti, who celebrated triumphs in theater with Benno Besson. Weiler, who had meanwhile returned to the Dresden Studio, understood THE TALE OF CALIF STORK (DIE GESCHICHTE VOM KALIF STORCH, 1982/83), based on the fairy tale of the same name by Wilhelm Hauff, as a cinematic warning signal to the people in power in the GDR. He portrayed a ruler who would not shy away from danger, to learn about the concerns and desires of the people. With MEMORY OF A CONVERSATION (ERINNERUNG AN EIN GESPRÄCH, 1984), Weiler brought the figures of the Pergamon Altar to life.

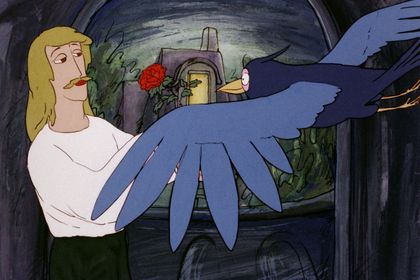

THE SEARCH FOR THE BIRD TULIPAN (DIE SUCHE NACH DEM VOGEL TURLIPAN, 1976), based on a poem by Peter Hacks and with music by Claude Debussy, became what is perhaps Kurt Weiler's most beautiful film. It tells the legend of a scientist in search for a legendary bird. Although he does not find it, he makes countless other discoveries on his journey. This plea for adventure and cosmopolitanism was created by using everyday objects: toothbrushes and other brushes stand for a forest, shards of porcelain for glittering natural resources, and the hero rises through a sky full of pink balloons, which also allows for erotic associations. The main character's love of discovery corresponds to the director's imagination.

THE STORY OF CALIF STORK (DIE GESCHICHTE VOM KALIF STORCH, Kurt Weiler, 1982-83) Photography: Rolf Hofmann

MEMORY OF A CONVERSATION (ERINNERUNG AN EIN GESPRÄCH, Kurt Weiler, 1984) Photography: Rolf Hofmann

Risks and bans

In the mid-1960s, the Dresden Studio produced a few aesthetic surprises in addition to the usual affectionate, but often somewhat conventional cartoons. Thus an artistic maverick like Heinz Nagel, who had studied at the Prague Film School FAMU and had made his debut in 1964 with the flat-figure film THE LITTLE FROG AND HIS TIRE (VOM FRÖSCHLEIN UND SEINEM REIFEN), was able to gain a foothold here, albeit with difficulties. There were no naturalistic figures to be seen in this film, but rather lines, squiggles and circles, the interaction of which resulted in a poetic fascination. From that point on, Nagel created his own universe, sometimes thwarted but never fully deterred: among other things, he animated three MUSICAL ARABESQUES (MUSIKALISCHE ARABESKEN, 1979-1982) using color pencils. He turned musical pieces such as Robert Schumann's “Dreaming” or Suite No. 4 by the GDR rock group "Bayon" into sensual and visual experience through abstract plays of color and light. Nagel's art followed the tradition of German trick classics such as Oskar Fischinger and Walther Ruttmann. Nagel found a small, committed circle of fans, but was rather neglected when it came to theatrical distribution because his films did not correspond enough to conventional viewing habits.

Animation film production for adults was already gaining momentum in the 1960s, and the canon of animation forms was gradually being expanded. The cut-out film HELLO, MR. H. (GUTEN TAG, HERR HITLER, Katja and Klaus Georgi, 1965) used collaged material from photos, newspaper clippings and painted figurines to imagine what would happen if Adolf Hitler reappeared in West Germany after the statute of limitations for Nazi crimes had expired. It was a bitter satire. One of the first co-productions between the DEFA Studio and the Moscow Soyuzmultfilm Animation Studio was the cut-out film A YOUNG MAN NAMED ENGELS: A PORTRAIT IN LETTERS (EIN JUNGER MANN NAMENS ENGELS - EIN PORTRÄT IN BRIEFEN, Klaus and Katja Georgi, Fjodor Chitruk, Wadim Kurtschewski, 1970), based on letters, diary fragments and drawings by the young Friedrich Engels. The film takes the famous man off his pedestal and shows him as an impetuous and loving contemporary who observes his surroundings closely. Perfectly created co-productions were also realized with the Italian company Corona Cinematografica: SPINDEL, WEAVER’S SHUTTLE AND NEEDLE (SPINDEL, WEBERSCHIFFCHEN UND NADEL, Katja Georgi, 1973), THE PRINCESS AND THE GOATHERD (DIE PRINZESSIN UND DER ZIEGENHIRT, Bruno J. Böttge, 1973) and LUCKY CHILDREN (GLÜCKSKINDER, Klaus Georgi, 1974/75). The Chilean emigrant Juan Forch, later a high-ranking campaign manager in Latin America, encapsulated the relationship between US politics and the gun lobby in his cut-out film A REPORT FOR WORLD HISTORY – USA 200 (EINE REPORTAGE FÜR DIE WELTGESCHICHTE - USA 200, 1975/76). Together with Jörg Herrmann, Michael Börner and Lothar Barke, Forch created several agitating shorts against the fascist Pinochet coup in Chile, as well as two adaptations of Latin American legends: LAUTARO (LAUTARO, 1977) and ROSAURA (ROSAURA, 1978).

THE LITTLE FROG AND HIS TIRE (VOM FRÖSCHLEIN UND SEINEM REIFEN, Heinz Nagel, 1964) Photography: Heinz Nagel

A YOUNG MAN NAMED ENGELS: A PORTRAIT IN LETTERS (EIN JUNGER MANN NAMENS ENGELS - EIN PORTRÄT IN BRIEFEN, Katja und Klaus Georgi, Fjodor Hidruk, W. Kurtschewsky, 1970) Photography: Manfred Henke, Werner Baensch

One of the major international projects the animation studio was involved in was a thirteen-part German-Czech puppet series about the mountain ghoul Rübezahl. The first film in the series, RÜBEZAHL AND THE SHOEMAKER (RÜBEZAHL UND DER SCHUSTER, Stanislav Látal), was released in 1976. A film proposal made by Krátký Film was not endorsed by DEFA. The animators from Prague tried to get their Dresden colleagues interested in a puppet film adaptation of Franz Kafka’s “The Island of Exiles.” The Czechs tried very hard! The concept was a film that would stand up “against the revisionist Kafka interpretation of Goldstücker and his followers” and take a stand against “renegades in the Czechoslovakia and the GDR” and stand entirely “in the sense of continuing the common ideological offensives based on the decisions of the ideology secretaries of the central committees of the fraternal socialist parties.”[3] However, DEFA did not want to step on this political slippery slope; the proposal remained in the drawer.

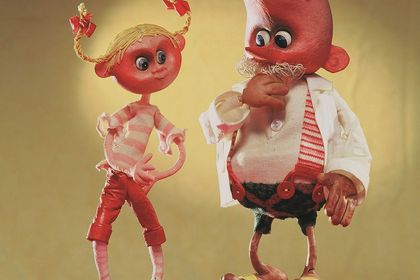

Bruno J. Böttge and Jörg Herrmann recall the friendship between Karl Marx and Paul Lafargue in their film DEAR MOHR (LIEBER MOHR - PERSÖNLICHE ERINNERUNGEN AN KARL MARX VON PAUL LAFARGUE, 1972), using silhouettes, flat figures and photos. In the puppet animation film LIFE AND ACTIONS OF THE FAMOUS KNIGHT SCHNAPPHANHNSKI (LEBEN UND THATEN DES BERÜHMTEN RITTERS SCHNAPPHAHNSKI, 1976/77), based on the book of the same name by Georg Weerth, director Günter Rätz, condenses the biography of a Prussian-Silesian nobleman and his decline and questionable triumph. The film received a great deal of international attention. Ina Rarisch made the colorful puppet animation LITTLE ZACHES CALLED ZINNNOBER (KLEIN ZACHES, GENANNT ZINNOBER, 1977/78) based on the eponymous novel by E. T. A. Hoffmann. And for NOVELLA (NOVELLE, 1974), based on the work of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Katja Georgi worked with doll’s hands and heads made of fine porcelain produced in the Meissen manufactory especially for DEFA. Georgi’s later works, such as THE BEAUTY AND THE ANIMAL (DIE SCHÖNE UND DAS TIER, 1976), FAUST’S FIRE (DAS FEUER DES FAUST, 1980/81) and DWARF NOSE (ZWERG NASE, 1985), became the highlights of romantic puppet animation, although she had to wait until the early 1970s to finally adapt romantic literature that was long considered reactionary in the official GDR literary historiography. With THE MYRTLE LADY (DAS MYRTENFRÄULEIN, 1988), she once again made a plea for the preservation of nature: the beauty of a tree and a bird brings a prince trapped in a cold art world back to life...

LITTLE ZACHES CALLED ZINNNOBER (KLEIN ZACHES, GENANNT ZINNOBER, Ina Rarisch, 1977-78) Photography: Rolf Hofmann

FAUST’S FIRE (DAS FEUER DES FAUST, Katja Georgi, 1980-81) Photography: Peter Pohler

Affected by the ban was the suggestive cartoon …AND BEWARDS THE END (... UND BEDENKT DAS ENDE, Lothar Friedrich, 1981–1983), in which two fortress towers wandering around the earth devour nature and destroy all life. This motif, which both refers to political world systems and uncompromisingly points to an imminent apocalypse, was too imprecise in its ideological aim for the cultural functionaries of the GDR. Friedrich's film was not released in cinemas until 1990, after the director's suicide. Conversely, the materials for Otto Sacher's THE BOMB (DIE BOMBE, 1963), a film that was canceled because of its pacifist tendencies (Sacher had turned against the atomic bomb in general), are lost. And director Günter Rätz also had to experience censorship: the cut-out film MISTER TWISTER (MISTER TWISTER), an anti-racist satire, was banned in January 1962, and the studio had to repay the costs of 90,000 marks that the film distributor had paid in advance. The story of a rich, white American family that is confronted with people of color on a vacation trip to the Soviet Union did not realistically reflect the conditions in the USSR and contained massive political errors, according to the approval committee.

The possibility of commenting on current events with socially critical and polemical material, as in Polish, Czechoslovak and, above all, Yugoslav animation films, was rather limited at DEFA for a long time. Ideological control was taken very seriously in the studio, especially in the early decades, and furthermore every film had to pass state approval in Berlin. Critique was often limited thematically to individual “negative” contemporaries such as loafers or drunkards. Depicting systemic conflicts led to requested cuts, as in the case of Herbert Löchner's hand puppet film THE STONE AGE LEGEND (STEINZEITLEGENDE, 1965), which made fun of official bureaucracy. And Rätz's project ASSISTANT MAILMAN SÄBELEIN (DER POSTHILFSBOTE SÄBELEIN, 1964), a satire against bureaucracy, was shelved shortly before shooting even started.

Targeting economic shortages was also not necessarily appreciated. One of the episodes of the popular animated series FATHER AND FAMILY (VATER UND FAMILIE, Sieglinde and Will Hamacher, Lothar Barke, Werner Kukula, Otto Sacher, Klaus Georgi, Karl-Heinz Hofmann, Christian Biermann, Hans-Ulrich Wiemer, 1969-1977), shows how a family man occasionally steals things that are not available in stores from his workplace in order to expand his allotment. The satirical highlight was meant to be the main character dragging a huge electricity pylon home. But that was too much. The mast shrank to a small hanging lamp.

... AND BEWARDS THE END (... UND BEDENKT DAS ENDE, Lothar Friedrich, 1981-82) Photography: Helmut Krahnert

THE STONE AGE LEGEND (STEINZEITLEGENDE, Herbert Löchner, 1965) Photography: Wolfgang Bergner

Einmart, Fridolin and others

Above all, it was thanks to the dramaturg Marion Rasche, who worked in Dresden from the mid-1970s and who had also been chief dramaturg since 1981, that people "from outside" the core of the studio were given the opportunity to work at the Gorbitzer Höhen. The Leipzig painter and graphic artist Lutz Dammbeck created some outstanding DEFA cartoons. His EINMART (EINMART, 1980/81) in particular became an insider tip in GDR film clubs and among intellectuals: based on Roland Topors and René Laloux' LA PLANÈTE SAUVAGE (DER WILDE PLANET, 1973), which was also occasionally shown in the GDR, Dammbeck designed a future world covered in craters, where mutated human beings are ruled by a huge black beast and prevented from any attempt to fly. Einmart, with its huge ears protruding into the landscape and dangerous ganglia shooting out of the ground, conjured up the danger of a surveillance state in which individuals could at best live out their utopias in dreams. The fact that Dammbeck was not only targeting a real socialist society, but humanity in general, was almost overlooked by audiences, and the film was interpreted virtually exclusively as a parable for the GDR.

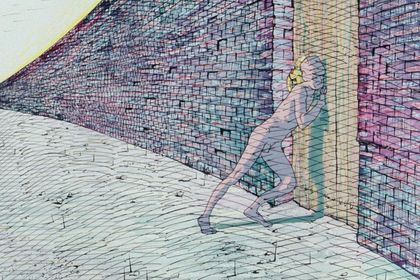

Dammbeck had already used the motif of flying and failure in his 1979 animated film THE TAILOR OF ULM (DER SCHNEIDER VON ULM), shot in the Potsdam Studio for Documentary Films. Based on the Brecht poem of the same title, the director portrayed a person who rebels against the directives of those in power and tries to take off from the ground. After a few more animated works, including THE DISCOVERY (DIE ENTDECKUNG, 1982/83) and THE FLOOD (DIE FLUT, 1986), Dammbeck left the GDR in February 1986. In addition to his state-produced films, he also made some independently produced Super-8 productions, such as METAMORPHOSES I (METAMORPHOSEN, 1978) and HOMMAGE TO LA SARRAZ (HOMMAGE À LA SARRAZ, 1981), in which he played with material in a much more radical way than in his DEFA films, dispensing with a conventional fable and presenting an associative montage made of traditional, alienated and newly filmed components. Dammbeck's "officially" registered DEFA project of an animated adaptation of the classic Hercules legend could not be realized in the GDR; it was made under the title THE CAVE OF HERCULES (HERAKLES HÖHLE, 1990) as an experimental film for West German television.

EINMART (EINMART, Lutz Dammbeck, 1980-81) Photography: Hans Schöne

THE FLOOD (DIE FLUT, Lutz Dammbeck, 1986) Photography: Lutz Kleber

Other GDR artists who broke with the formal DEFA canon in their privately produced experimental films were also brought by Marion Rasche to the Dresden DEFA Studio, including painter Helge Leiberg. He created the cartoon FRIDOLIN, THE BUTTERFLY (FRIDOLIN, DER SCHMETTERLING, Helge Leiberg, Alexander Reimann, 1982), which turned out to be an insect fairy tale combined with an old man's sexual fantasy and dream of omnipotence. Leiberg also created the collage figures for SIRENS (SIRENEN, Klaus Georgi, 1983/84), in which mythical creatures with bird bodies and women's heads perish from environmental pollution. However, Leihberg’s did not get the go-ahead for his earlier DEFA project MISTER SCHULZE (1981), a story about a man who is being bullied by his wife and boss and who gets drunk, turns into a rooster and finally rebels. The cartoon JUCHU (JUCHU, Klaus Georgi, 1983), on which Leiberg worked as a designer, was also not approved. In 1988, the film was finally released in a different form under the new title LOGICAL SERIES (LOGISCHE FOLGE). The film tells the story of a man who shoots down everything he encounters in the woods and fields with increasing euphoria. The fact that he was the only target of his killing spree left at the end seemed too pessimistic to those responsible for film in the GDR. Leiberg left the GDR two years before Dammbeck.

After all, such “restless young people,” including the painter Gudrun Trendafilov (RACEWAY (LAUFBAHN, 1982–1984)), the caricaturist Rainer Schade (SITIS (SITIS, 1989)), the photo and graphic artist Ulrich Lindner (OVER TIME (ZEITVERLÄUFE, 1989)), the Berlin painter Wolfgang Mond (FELLOW PEOPLE (MIT MENSCHEN, 1979)) and Thomas Stephan (THE ROCKING CUBE (KUBUS IM ROCK, 1988/89)), brought new colors and shapes into the Dresden animation canon. Finally, Sieglinde Hamacher, who worked in the studio for many years, surprised audiences with short, cheeky parables about human weaknesses and social grievances (A PEACEFUL DAY (EIN FRIEDLICHER TAG, 1984/85); THE SOLUTION (DIE LÖSUNG, 1987/88); BASIC NEED, OR WORKING IS FUN (LEBENSBEDÜRFNIS ODER: ARBEIT MACHT SPASS, 1988/89)). Otto Sacher, who, like Kurt Weiler and Günter Rätz, was a mentor to many young people, tried his hand at picturesque films such as AT THE WINDOW (AM FENSTER, 1978) or THE LION AND THE BIRD (DER LÖWE UND DER VOGEL, 1982). Günter Rätz’s film FEAR (ANGST, 1981/82) was an impressive study of the persecution of the Jews during the Nazi era. And Horst J. Tappert had classic silhouetted figures act in front of an abstract, colored background in HANS, MY HEDGEHOG (HANS, MEIN IGEL, 1984/85). In the 1980s, Dresden animated films had become more thematically diverse and formally bolder.

SITIS (SITIS, Rainer Schade, 1989) Photography: Helmut Krahnert

THE SOLUTION (DIE LÖSUNG, Sieglinde Hamacher, 1987-88) Photography: Brigitte Schönberner

And finally, feature-length films for a wider public were produced at the studio. Günter Rätz’s puppet film THE FLYING WINDMILL (DIE FLIEGENDE WINDMÜHLE, 1978-81) was particularly successful. The director tells an ironic science fiction fable that is linked to musical elements and brings together memorable characters such as the girl Olli, the dog Pinkus, the crocodile Susi and the talking horse Alexander to form a remarkable group. There are also bizarre scenes, such as the dance of the frogs or the plants spitting fried eggs. Rätz tells of the characters’ journey into space in a windmill, from which Susi, who had previously brought home a bad report card, returns to earth purified. The variety of colors and shapes, the plot twists and the playful handling of the wire puppets made the film an audience favorite. It received prizes at the Golden Sparrow Children's Film Festival in Gera and at the Vienna Children's Film Festival. Then Rätz turned to the full-length Karl May adaptation THE TRAIL LEADS TO SILVER LAKE (DIE SPUR FÜHRT ZUM SILBERSEE, 1985-1989) and began preparing the project "The Spirit of Llano Estacado," also based on a story by Karl May. But after about 600 meters had already been filmed, the project was frozen. The studio management ordered the work to be stopped and used approximately 600,000 marks from the film's budget for debt relief in the context of the monetary union.

THE FLYING WINDMILL (DIE FLIEGENDE WINDMÜHLE, Günter Rätz, 1978-81) Photography: Helmut May

THE TRAIL LEADS TO SILVER LAKE (DIE SPUR FÜHRT ZUM SILBERSEE, Günter Rätz, 1985-89) Photography: Rudolf Uebe

The end of the studio

In 1990/91, the Dresden Studio, which had produced hundreds of commissioned works for GDR television and other clients in addition to cinematic productions, was closed. In the GDR, the studio had a prominent position as one of the only producers of animation films. After the studio’s closure, the employees found themselves exposed to an international, highly competitive market. There were proposals for saving the studio through technical upgrades while at the same time massively reducing jobs. But all such plans only existed on paper, and many of the approximately 240 full-time directors, dramaturgs, animators, editors and cameramen became unemployed. Some retired, a few took on new jobs. Their last films, which were still released under the "DEFA" label, remained widely unknown.

But some of these late cinematic works also artfully make the atmosphere of their time transparent, such as Sieglinde Hamacher's cartoon OCCUPATION (OKKUPATION, 1990), in which a fat man settles into the apartment of a thin man and drives him out of his own four walls. In THE BREAKDOWN (DIE PANNE, Klaus Georgi, Lutz Stützner, 1989), a small Trabant car pulls an entire state cordon, including limousines, tanks and squadrons of motorcycles, out of a pothole on a highway. In MONUMENT (MONUMENT, Klaus Georgi, Lutz Stützner, 1989) a crowd cheers a monument, regardless of whether it faces one way or the other. In C’EST LA VIE (C’EST LA VIE, Christian Biermann, 1988/89) a beautiful woman beckons a lover to approach her, but when she bites his neck, she proves to be a veritable vampire. Thomas Stephan's cut-out film NOAH (NOAH, 1990) describes the biblical legend as a timeless parable: the title character stands out from the crowd of passive fellow citizens by building an ark and is able to save their lives during the unexpected flood. Gabor Steisinger's QUICK ANIMATION (QUICK ANIMATION, 1989) then led to pop and rap and to an animated modernity. The DEFA Studio for Animation Films escaped the imminent leap from manual work to digital technology.

C'EST LA VIE (C'EST LA VIE, Christian Biermann, 1988-89) Photography: Steffen Nielitz

MONUMENT (MONUMENT, Lutz Stützner, Klaus Georgi, 1989) Photography: Helmut Krahnert

The cut-out fairy tale, THE WOLF AND THE SEVEN LITTLE KIDS (DER WOLF UND DIE SIEBEN GEISSLEIN, 1990/91), in which Otto Sacher, one of the founding fathers of the studio, directed in a traditional and proven manner, is the last production of the DEFA Studio. Today, the legacy of the studio is lovingly cared for by the German Institute for Animated Film (DIAF). Housed in a former Ernemann factory building in Dresden, thousands of pieces—photos, drawings, sketches, dolls, sets, screenplays, and even entire legacies—are kept there. Numerous memories of former employees were digitally recorded. Through exhibitions, film evenings and publications, the DIAF, often in association with the DEFA Foundation, helps to keep Dresden's animation films alive. Because many of these films are now also available in digitized form, nothing stands in the way of their use in cinemas and on television, on streaming platforms and on DVD.

written by Ralf Schenk (Dezember 2021)

Endnotes

- Kurt Weiler: Gedanken zum Puppentrickfilm. Eine Anregung zur Diskussion. In: Deutsche Filmkunst, East Berlin, No. 5/1954. 17–19.

- Günter Agde: Kurt Weiler: Trick- und Werbefilme aus zwei Jahrzehnten. In: Filmblatt, Berlin, No. 7, Spring/Summer 1998. 8–10.

- See Volker Petzold: Zwischen Friedrich Engels und Berggeist Rübezahl. In: Ralf Schenk, Sabine Scholze (ed.): Die Trick-Fabrik. DEFA-Animationsfilme 1945–1990. Berlin 2003. 306. – Eduard Goldstücker (1913–2000) was a Czech literary historian, publicist and diplomat who campaigned for political reforms and emigrated to Great Britain in 1968.